Material Interventions into Immaterial Landscapes

Intervention II: In the Still of the Night

Material Interventions into Immaterial Landscape Intervention II: In the Still of the Night

Angela Anderson (2021)

Material Interventions into Immaterial Landscapes

Intervention II: In the Still of the Night

Print, Postcards, Website

Angela Anderson (2021)

Status Project Proposal: The Stuttgart Department of Property and Construction did not grant permission for this project, citing reasons of sanctity and monument preservation.

This intervention was planned as a site-specific installation in the immediate vicinity of Academy Schloss Solitude. As a public artwork, in the form of a painted sign, it was meant to serve as a counterpoint to the Kameraden-Gedenkstein, a monument commemorating WWII German army soldiers from Stuttgart who died during their assignments to various parts of Europe, including France and Poland.

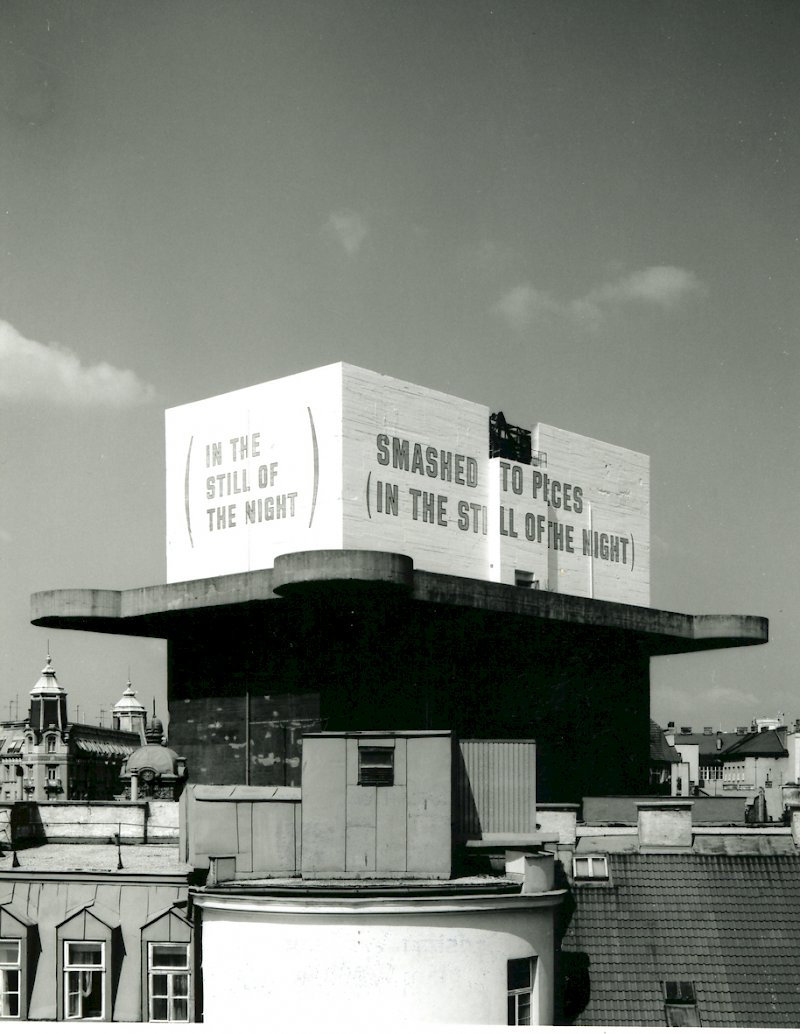

The text on the sign is taken from the iconic work Smashed to Pieces (In the Still of the Night) by the NYC based conceptual artist Lawrence Weiner. Weiner’s original artwork was installed on top of one of the six massive flak towers built in Vienna during WWII as bomb shelters against allied air attack. The original work was commissioned by the Wiener Festwochen in 1991, and was meant to be on view for five years, but was recognized by the city of Vienna as an official memorial against war and fascism, and thus was not removed. In 2019, however, the Vienna Aquarium, which is now located in same the flak tower, decided to paint over the artwork while renovating the tower. This erasing of a statement which itself served to prevent the erasing of the memory of the brutality of the Holocaust, was a source of great controversy, which has yet to be resolved.

Since seeing the artwork on my very first trip to Vienna many years ago, this phrase has never left my mind. It has a double meaning, reminding of the brutality and violence of war, and in particular the Holocaust and specifically the Kristallnacht pogrom of 1938, and also points to the desire to remove the symbols of racist and colonial violence that are left over, in a similar way that statues of colonial figures have recently been felled, from South Africa, to the UK, to the US and beyond.

Flakturm in Esterházypark in Vienna: Zerschmettert in Stücke (im Frieden der Nacht) / Smashed to pieces (in the still of the night) (1991) by Lawrence Weiner. Photo: Christian Wachter

My proposed installation of a sign at the location of the stuttgart.im-bild.org/fotos/gedenksteine-staetten/kameraden-gedenkstein-an-der-solitude was intended as a discursive intervention into the historical memory constructed by the stone monument and accompanying statement which make up this Ehrenmal (a monument in honor of something). The Kameraden Gedenkstein was installed in 1972, twenty seven years after the end of WWII, and twenty three years before the Wehrmacht Exhibition would make the German Army’s complicity in war crimes during WWII explicit. While the text on the accompanying sign could perhaps be interpreted as a warning against future wars (“Als Mahnung für die Lebenden”), the memorial makes no reference to the fact that Germany was the aggressor in this war, and no reference to the crimes against humanity that were committed during this war, including by members of the German army.

The text of the Kameraden-Gedenkstein explains the shape of the stone monument as representing the German people, who are lamentably divided (East & West Germany), but only superficially (“Er ist versehrt und zerspalten wie unser Volk doch nicht bis auf den Grund”). Reading this sentence, one must ask who exactly these German people are who are being spoken to in this text. Does it include those whose lives were brutally taken away by the same fascist regime the soldiers who are remembered by this monument were fighting for?

Kameraden-Gedenkstein an der Solitude. Commissioned by Kameradenhilfswerk (1972). Featured here with a fresh wreath in Dec, 2020. Photos: Angela Anderson (2020)

The color of my proposed sign, a deep fuschia-pink, references the pink triangle which gay men and other “sexual deviants” were forced to wear in WWII Nazi concentration camps, and which has since been adopted as a symbol of gay liberation. Ironically, the stone monument to WWII soldiers features a hollow section in the form of a downward pointing triangle, the exact shape used by the Nazi regime to label prisoners according to a color scheme, pink being one of those colors.

Sign pointing to the Kameraden-Gedenkstein “Ehrenmal” next to the Solitude Cemetary. Photos: Angela Anderson (2021)

With this work, my intention was to make a statement against war and its glorification, as well as the revisionist historical memory it affirms. Quite ironically, the Stuttgart Department of Property and Construction did not grant permission for this project, citing reasons of sanctity and monument preservation, in part because the Solitude Cemetary is located approximately 50m from this monument. Constructed as a military cemetary in 1866, one of the people buried in this cemetary is the German sculptor and painter, and former director of the Stuttgart Academy of Fine Arts Fritz von Graevenitz (1892-1959).

Graevenitz Museum, Schloss Solitude, Stuttgart. Photo: Angela Anderson (2021)

From a military family, Fritz von Graevenitz had his workshop between the Academy Schloss Solitude and the Solitude Cemetary, which is now a museum. This small museum, which contains mainly sculptural work and painting, is free and open to the public on certain days of the week. Little did I know upon visiting the museum, that Fritz von Graevenitz was actually very closely connected to National Socialism, and that amoung his many sculptures produced in the service of Nazi Germany was a bronze cast bust of Adolph Hitler in 1937 (which a quick web search will tell you).

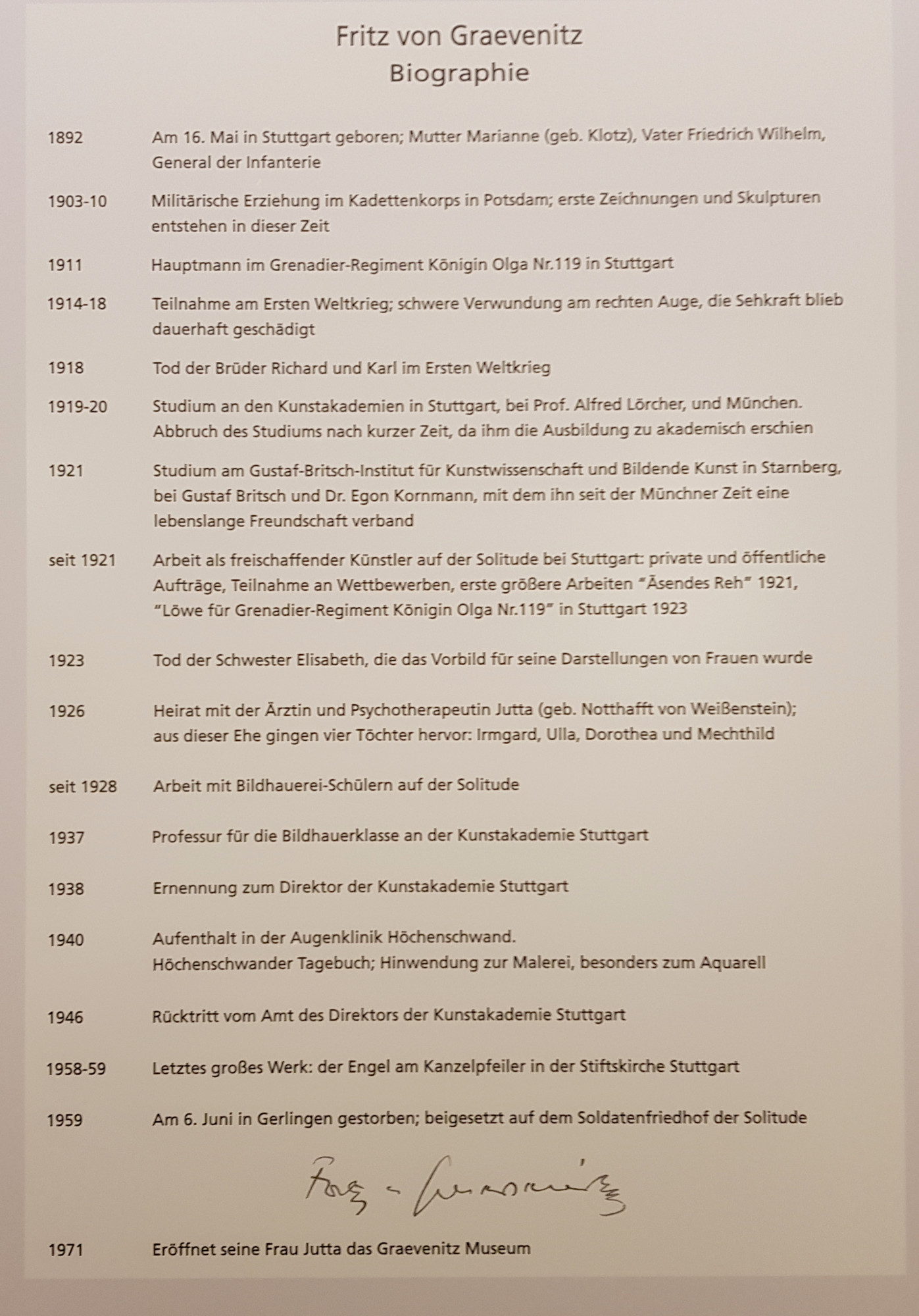

Biography of Fritz von Graevenitz as displayed at the Graevenitz Museum, Stuttgart. Photo: Angela Anderson (2020)

Unfortunately, this information is nowhere to be found within the museum itself. The biography that hangs in the museum makes no reference whatsoever to Fritz von Graevenitz’s work as an artist supporting the fascist National Socialist regime, as can be seen on this photograph above. Unsuspecting tourists who wander into the museum would never know, without further research, that the artist was an active participant in the creation of Nazi propaganda in the form of large-scale public sculptures between 1938 & 1945.

My proposed installation was in reaction to these two locations in the immediate proximity of Academy Schloss Solitude, locations of what at best could be called selective memory, and perhaps more accurately, historical revisionism, which blatantly downplay and/or ignore the gravity and brutality of the crimes against humanity committed by the German National Socialist regime as well as the German Army before and during WWII.